Mega888 Online Casino Malaysia Duitnow Slot Ewallet Casino TNG

Selamat datang ke Mega888, platform kasino dalam talian yang semakin popular di Malaysia. Mega888 menawarkan pengalaman kasino dalam talian yang menakjubkan. Kami akan jelajahi keistimewaan Mega888, termasuk penggunaan e-wallet TNG dan sistem pembayaran DuitNow.

Mega888 adalah pilihan utama pemain kasino dalam talian di Malaysia. Ia menawarkan kepelbagaian permainan dan kemudahan serta keselamatan transaksi. Dengan e-wallet TNG dan sistem DuitNow, transaksi deposit dan pengeluaran menjadi lebih cepat dan selamat.

Kami akan memberi panduan lengkap tentang mendaftar dan menggunakan DuitNow. Anda juga akan belajar mengurus e-wallet TNG dan menikmati permainan slot terbaik. Kami akan berkongsi tips untuk meningkatkan peluang kemenangan anda. Siap untuk menjelajahi dunia kasino dalam talian ini?

Intisari Utama

- Mega888 adalah platform kasino dalam talian terkemuka di Malaysia

- Menggunakan e-wallet TNG dan sistem pembayaran DuitNow untuk deposit dan pengeluaran yang mudah dan selamat

- Menawarkan pelbagai permainan slot dan kasino langsung yang menarik

- Mempunyai ciri-ciri keselamatan yang ketat untuk melindungi akaun pengguna

- Terdapat pelbagai bonus dan promosi menarik untuk para pemain

Pengenalan Kepada Platform Mega888 Malaysia

Mega888 adalah platform kasino dalam talian yang sangat popular di Malaysia. Ia mula beroperasi di Malaysia sejak tahun 2015. Sekarang, Mega888 menjadi pilihan utama bagi banyak pemain judi di Malaysia, Singapura, dan Thailand.

Sejarah Mega888 di Malaysia

Mega888 mula beroperasi di Malaysia pada tahun 2015. Dari awal, ia sudah menjadi salah satu platform permainan dalam talian yang paling disegani. Syarikat ini kini memegang lebih daripada 90% bahagian pasaran di Malaysia.

Ciri-ciri Utama Platform

- Menawarkan pelbagai jenis permainan termasuk slot, kasino langsung, dan perjudian sukan.

- Menyediakan antara muka pengguna yang mudah digunakan dan mesra.

- Mempunyai pilihan pembayaran yang fleksibel termasuk e-wallet, kad kredit, dan pemindahan bank.

- Sentiasa mengeluarkan permainan dan promosi baharu untuk mengekalkan pengalaman yang segar bagi para pemain.

Lesen dan Keselamatan

Mega888 beroperasi di bawah lesen yang sah. Ia mengikuti piawaian keselamatan industri yang tinggi untuk melindungi maklumat dan dana pengguna. Teknologi enkripsi canggih digunakan untuk memastikan setiap transaksi kewangan dan maklumat peribadi berada dalam keadaan selamat.

| Statistik Penting |

Angka |

| Bahagian Pasaran Mega888 di Malaysia |

Melebihi 90% |

| Pemain dari Malaysia, Singapura, dan Thailand |

80% |

| Jumlah Muat Turun Aplikasi Mega888 |

Lebih 1 juta |

Mega888 telah membuktikan dirinya sebagai platform kasino dalam talian yang boleh dipercayai dan berprestij di Malaysia. Dengan sejarah yang kukuh, ciri-ciri menarik, dan langkah-langkah keselamatan yang komprehensif, ia menjadi pilihan utama bagi peminat judi atas talian di rantau ini.

Cara Mendaftar Akaun Mega888

Bagi pemain yang ingin menikmati pengalaman akaun kasino dalam talian yang seru, pendaftaran Mega888 sangat mudah. Anda hanya perlu mengikuti beberapa langkah mudah untuk buat akaun di Mega888, yang sangat popular di Malaysia:

- Lawati laman web rasmi Mega888 dan klik butang "Daftar" di atas skrin.

- Isikan maklumat peribadi seperti nama, nombor telefon, alamat e-mel, dan nombor kad pengenalan.

- Pilih mata wang untuk akaun anda - Ringgit Malaysia (RM) atau Dolar Singapura (SGD).

- Cipta kata laluan yang selamat dan mudah diingat untuk melindungi akaun anda.

- Baca dan bersetuju dengan terma dan syarat Mega888.

- Selesaikan pengesahan akaun dengan menghantar salinan dokumen pengenalan diri yang sah.

- Setelah pendaftaran berjaya, anda boleh mula main permainan slot dan kasino menarik di Mega888.

Dengan mengikuti langkah mudah ini, anda akan dapat menikmati pengalaman bermain yang selamat dan menyeronokkan di akaun kasino dalam talian Mega888. Ingatlah untuk selalu menjaga keselamatan akaun anda untuk pengalaman terbaik!

| Statistik Mega888 |

Nilai |

| Bahagian Pasaran Permainan Slot di Malaysia |

Lebih 90% |

| Pemain dari Malaysia, Singapura, dan Thailand |

80% |

| Jumlah Muat Turun Aplikasi Mega888 |

Lebih 1 Juta |

Mega888 telah menjadi pemimpin industri perjudian dalam talian di Malaysia. Mereka menawarkan banyak permainan slot dan kasino yang menarik dengan bonus dan jackpot yang menggoda.

Sistem Pembayaran DuitNow di Mega888

Mega888 adalah platform kasino dalam talian yang popular di Malaysia. Mereka menawarkan pelbagai pilihan pembayaran untuk pengguna. DuitNow adalah salah satu kaedah pembayaran yang ditawarkan, memudahkan transaksi pembayaran dalam talian dan transaksi kasino.

Kelebihan Menggunakan DuitNow

Penggunaan DuitNow di Mega888 memberikan beberapa kelebihan:

- Proses transaksi yang pantas dan selamat

- Tiada bayaran tambahan atau yuran tersembunyi

- Integrasi yang lancar dengan sistem Mega888

- Kebolehpercayaan dan reputasi DuitNow sebagai platform pembayaran dalam talian

Langkah-langkah Transaksi DuitNow

Ini adalah langkah mudah untuk transaksi menggunakan DuitNow di Mega888:

- Log masuk ke akaun Mega888 anda

- Navigasi ke halaman deposit dan pilih DuitNow sebagai kaedah pembayaran

- Masukkan jumlah deposit yang dikehendaki

- Pilih bank anda dan log masuk ke akaun bank anda untuk mengesahkan transaksi

- Transaksi anda akan diproses dengan segera dan baki anda akan dikemaskini di Mega888

Dengan menggunakan DuitNow, pemain Mega888 dapat menikmati pengalaman pembayaran yang lancar. Ini memudahkan aktiviti transaksi kasino mereka.

slot ewallet mega888 TNG

Bagi peminat kasino dalam talian, menggunakan e-wallet untuk bermain slot di Mega888 sangat popular. Anda boleh menyambungkan akaun e-wallet Touch 'n Go (TNG) anda. Ini membolehkan anda menikmati keselesaan dan keselamatan pembayaran mudah alih semasa bermain slot Mega888.

Kelebihan menggunakan e-wallet TNG untuk slot Mega888 adalah:

- Transaksi yang pantas dan mudah

- Keselamatan terjamin dengan teknologi enkripsi

- Tiada had deposit minimum yang tinggi

- Pemantauan transaksi yang lebih baik

Untuk mula menggunakan TNG di Mega888, ikuti langkah-langkah berikut:

- Daftar dan pasangkan akaun TNG anda dengan akaun Mega888 anda.

- Pilih TNG sebagai kaedah pembayaran semasa membuat deposit.

- Masukkan jumlah deposit dan sahkan transaksi melalui aplikasi TNG.

- Dana akan terus dimasukkan ke dalam akaun Mega888 anda.

Dengan kemudahan e-wallet TNG, pengalaman bermain slot Mega888 anda akan lebih lancar dan selamat. Jangan tunggu lagi! Daftarkan akaun TNG anda sekarang dan mulakan bertaruh di platform Mega888 yang terpercaya.

Permainan Popular di Mega888

Mega888 adalah platform kasino dalam talian yang semakin popular di Malaysia. Ia menawarkan pelbagai permainan slot dan kasino langsung yang menarik. Pemain Mega888 suka bermain permainan slot popular seperti 918Kiss dan Kiss918.

Kasino langsung juga menjadi tarikan utama. Pelbagai pilihan seperti roulette, blackjack, dan baccarat tersedia.

Slot Games Terbaik

Mega888 menawarkan pelbagai permainan Mega888 yang menarik. Anda boleh menemui tema yang pelbagai dan peluang untuk meraih jackpot besar. Berikut adalah beberapa slot terpopular yang boleh anda cuba:

- Mega Moolah

- Gladiator

- Aztec Gems

- Dragons of the North

- Cleopatra

Live Casino Games

Bagi peminat kasino langsung, Mega888 mempunyai pilihan menarik. Anda boleh menikmati:

- Roulette

- Blackjack

- Baccarat

- Sic Bo

- Dragon Tiger

Dengan pelbagai pilihan permainan slot dan kasino langsung, Mega888 menawarkan pengalaman bermain yang menyeronokkan. Pemain di Malaysia pasti akan menikmati.

Panduan Deposit Menggunakan E-wallet

Untuk menikmati kasino dalam talian di Mega888, kaedah deposit penting. E-wallet semakin popular kerana mudah dan selamat. Kami akan tunjukkan cara deposit menggunakan e-wallet di Mega888.

Kelebihan Menggunakan E-wallet untuk Deposit

- Mudah dan cepat - Deposit dengan Touch 'n Go, GrabPay, dan Boost sangat ringkas.

- Keselamatan tinggi - E-wallet melindungi maklumat kewangan anda.

- Kawalan deposit - Anda boleh pantau deposit anda dengan mudah.

Langkah-langkah Deposit Menggunakan E-wallet

- Log masuk ke akaun Mega888 anda.

- Pergi ke "Deposit" di laman atau aplikasi Mega888.

- Pilih e-wallet seperti Touch 'n Go, GrabPay, atau Boost.

- Masukkan jumlah deposit yang dikehendaki.

- Ikut arahan untuk menyelesaikan deposit di aplikasi e-wallet.

- Log masuk ke aplikasi e-wallet dan sahkan transaksi.

- Dana akan masuk ke akaun Mega888 anda segera.

Dengan mengikuti langkah mudah ini, deposit ke Mega888 anda akan cepat dan selamat. Ini memastikan pengalaman bermain yang lancar dan selamat.

Keselamatan Transaksi di Mega888

Di Mega888, keselamatan kasino dalam talian sangat penting. Mereka mempunyai langkah keselamatan yang lengkap untuk melindungi pengguna. Ini termasuk melindungi dari aktiviti yang tidak sah.

Teknologi Enkripsi

Mega888 menggunakan enkripsi data canggih untuk melindungi transaksi kewangan. Data sensitif seperti maklumat kad kredit dan perbankan disulitkan dengan algoritma tinggi. Ini untuk memastikan keselamatan maksimum.

Sistem Verifikasi

Mega888 juga mempunyai sistem verifikasi pengguna yang ketat. Mereka memerlukan pengesahan identiti melalui pelbagai langkah. Ini termasuk pengesahan dua faktor untuk memastikan hanya pemilik akaun sah yang boleh mengakses dan melakukan transaksi.

Dengan teknologi enkripsi dan sistem verifikasi yang kuat, Mega888 mencipta persekitaran bermain yang selamat. Ini untuk semua pengguna di Malaysia.

Bonus dan Promosi Mega888

Di Mega888, pemain dapat menikmati banyak bonus dan promosi menarik. Ini memberikan nilai tambah kepada pengalaman mereka berjudi online. Dari bonus selamat datang yang menggoda hingga promosi musim yang mengujakan, Mega888 sentiasa memberi peluang kepada pemain untuk mendapatkan lebih banyak ganjaran.

Bonus Selamat Datang adalah tawaran khas untuk pemain baru. Bonus ini boleh digunakan untuk bermain pelbagai jenis permainan seperti slot dan kasino langsung. Ini memberikan pemain peluang untuk memulakan pengalaman perjudian mereka dengan lebih baik.

Bonus Deposit diberikan apabila pemain membuat deposit ke dalam akaun mereka. Jumlah bonus yang diberikan bergantung kepada jumlah deposit yang dibuat. Ini memberikan insentif kepada pemain untuk terus bermain dan meningkatkan deposit mereka.

| Jenis Bonus |

Perincian |

Syarat Tuntutan |

| Bonus Selamat Datang |

Bonus sehingga RM1,000 untuk pemain baru |

Daftar akaun baru dan buat deposit pertama |

| Bonus Deposit |

Bonus sehingga 150% daripada jumlah deposit |

Buat deposit ke dalam akaun dan penuhi syarat taruhan |

| Promosi Bermusim |

Bonus dan ganjaran istimewa seperti Birthday Month Bonus |

Ikuti syarat dan tempoh promosi yang ditetapkan |

Mega888 juga sering menjalankan promosi bermusim. Ini memberikan peluang kepada pemain untuk mendapatkan bonus dan ganjaran istimewa. Contohnya, promosi Birthday Month Bonus memberikan bonus tambahan pada bulan ulang tahun pemain.

Dengan pelbagai bonus kasino dan promosi Mega888, pemain boleh memanfaatkan tawaran khas ini. Ini meningkatkan peluang mereka untuk menang dan menikmati pengalaman perjudian yang lebih menguntungkan.

Panduan Bermain Slot Online

Bermain slot di Mega888 boleh sangat menyeronok dan menguntungkan. Namun, anda perlu strategi dan pengurusan modal yang baik. Ikuti panduan ini untuk meningkatkan peluang menang anda.

Tips Menang

Anda boleh meningkatkan peluang menang dengan mengikuti beberapa tips ini:

- Pelajari ciri-ciri permainan dan mekanisme pembayaran.

- Gunakan bonus dan promosi untuk tambah modal.

- Tetapkan had pertaruhan dan ikut disiplin.

- Jangan main tanpa strategi, main dengan bijak.

- Pilih permainan dengan RTP tinggi.

Strategi Pengurusan Modal

Pengurusan modal yang baik sangat penting untuk menang. Berikut adalah beberapa strategi yang boleh anda gunakan:

- Tentukan had deposit dan pertaruhan yang sesuai dengan kemampuan kewangan anda.

- Gunakan teknik 'bankroll management' untuk bahagikan modal ke beberapa sesi permainan.

- Elak risiko yang terlalu tinggi dengan tidak meningkatkan pertaruhan melebihi kemampuan anda.

- Belajar dari setiap pengalaman dan sesuaikan strategi anda jika perlu.

- Main dengan hati-hati dan bertanggungjawab untuk pengalaman yang seronok dan menguntungkan.

Dengan menerapkan strategi slot, tips menang, dan pengurusan wang yang betul, anda boleh meningkatkan peluang menang. Ingatlah untuk main dengan hati-hati dan bertanggungjawab.

Aplikasi Mega888 Mobile

Dunia aplikasi kasino mudah alih kini berkembang pesat. Mega888 mobile adalah salah satu platform terkemuka di Malaysia. Ia menawarkan banyak permainan dalam talian yang menarik dan menyeronokkan.

Para pemain boleh menikmati pengalaman kasino yang luar biasa hanya dengan menggunakan peranti mudah alih mereka.

Bagi mereka yang ingin mencoba Mega888 di mana sahaja dan bila-bila masa, aplikasi mudah alih Mega888 adalah pilihan yang ideal. Aplikasi ini boleh dimuat turun dengan mudah dan cepat. Anda boleh mendapatkannya dari Google Play Store atau App Store.

Ini memberikan akses lancar ke banyak permainan slot, kasino langsung, dan lain-lain.

Ciri-ciri Utama Aplikasi Mega888 Mobile

- Antara muka pengguna yang intuitif dan mesra pengguna

- Akses kepada semua permainan popular Mega888, termasuk permainan slot, kasino langsung, dan banyak lagi

- Proses log masuk dan daftar yang selamat dan mudah

- Kemampuan untuk melakukan deposit dan pengeluaran dengan cepat dan selamat melalui pelbagai kaedah pembayaran, termasuk ewallet seperti Touch 'n Go, Boost, dan GrabPay

- Notifikasi real-time mengenai promosi, bonus, dan acara terbaru

- Sokongan pelanggan 24/7 yang bersedia membantu dengan sebarang pertanyaan atau masalah

Aplikasi mudah alih Mega888 menawarkan ciri-ciri yang komprehensif dan pengalaman yang lancar. Ini menjadikannya pilihan unggul bagi peminat permainan dalam talian di Malaysia. Anda boleh menikmati kemudahan dan keseronokan aplikasi kasino mudah alih Mega888 di mana saja dan bila-bila masa.

Perbandingan E-wallet di Mega888

Mega888 adalah platform kasino dalam talian terkemuka di Malaysia. Ia menawarkan pelbagai pilihan e-wallet untuk pembayaran. Tiga e-wallet utama adalah Touch 'n Go, GrabPay, dan Boost. Setiap e-wallet mempunyai kelebihan dan kekurangan yang berbeza.

Touch 'n Go

Touch 'n Go adalah e-wallet paling popular di Malaysia. Ia digunakan banyak di Mega888. Ia menawarkan had transaksi tinggi dan proses pembayaran yang cepat.

Pengguna perlu pastikan akaun Touch 'n Go mereka mempunyai baki yang cukup. Ini penting sebelum deposit ke Mega888.

GrabPay

GrabPay semakin popular di kalangan pemain Mega888. Ia menawarkan pengalaman pembayaran yang mudah dan cepat. Had transaksi GrabPay juga fleksibel.

Pemain perlu berhati-hati dengan yuran tambahan GrabPay. Ini mungkin dikenakan untuk sesetengah transaksi.

Boost

Boost adalah e-wallet lain yang diterima di Mega888. Ia mempunyai proses transaksi yang cepat dan had yang munasabah. Namun, kurang popular berbanding Touch 'n Go dan GrabPay.

Pemain mungkin menghadapi cabaran dalam menggunakan Boost di Mega888.

| Ciri-Ciri |

Touch 'n Go |

GrabPay |

Boost |

| Had Transaksi |

Tinggi |

Fleksibel |

Munasabah |

| Kelajuan Pemprosesan |

Pantas |

Pantas |

Pantas |

| Keselamatan |

Baik |

Baik |

Baik |

| Populariti di Mega888 |

Tinggi |

Sederhana |

Rendah |

Ketiga e-wallet ini menawarkan pengalaman pembayaran yang baik di Mega888. Pemain perlu mempertimbangkan kelebihan dan kekurangan setiap e-wallet. Ini penting untuk memilih pilihan terbaik.

Sokongan Pelanggan 24/7

Di Mega888, kami tahu betapa pentingnya khidmat pelanggan yang cepat. Kami menawarkan sokongan 24 jam setiap hari, 7 hari seminggu. Ini untuk memastikan anda dapat bantuan kapan saja.

Pasukan kami yang berpengalaman siap membantu anda. Mereka akan menjawab pertanyaan atau menyelesaikan masalah anda cepat. Kami ada untuk membantu dengan khidmat pelanggan terbaik, sama ada soalan teknikal atau nasihat.

- Hubungi kami melalui talian telefon 24/7

- Hantar e-mel kepada bantuan Mega888 untuk pertanyaan bertulis

- Layari laman web kami untuk sokongan dalam talian dan Soalan Lazim

Kami ingin anda menikmati pengalaman bermain yang lancar dan menyeronok. Jangan ragu untuk menghubungi kami jika anda butuh bantuan.

| Kaedah Sokongan |

Waktu Operasi |

Tindak Balas Purata |

| Telefon |

24 jam sehari, 7 hari seminggu |

20 saat |

| E-mel |

24 jam sehari, 7 hari seminggu |

6 jam |

| Borang Hubungi dalam talian |

24 jam sehari, 7 hari seminggu |

2 jam |

"Sokongan pelanggan yang cepat dan mesra pengguna adalah keutamaan kami di Mega888."

Tips Keselamatan Akaun

Membina keselamatan akaun dalam talian yang kukuh sangat penting. Ini untuk melindungi data anda di kasino selamat seperti Mega888. Berikut adalah beberapa tips untuk meningkatkan keselamatan akaun anda:

- Pilih kata laluan yang kuat dan unik untuk setiap akaun anda. Jangan gunakan maklumat peribadi yang mudah diteka.

- Aktifkan pengesahan dua faktor untuk tambahan lapisan keselamatan semasa log masuk.

- Waspadalah terhadap e-mel, mesej, atau panggilan telefon yang mencurigakan. Mereka mungkin cuba mendapatkan maklumat sensitif anda.

- Elak menggunakan rangkaian awam yang tidak selamat atau mengakses akaun anda di tempat awam.

- Tetapkan dinyahaktifkan akaun Mega888 anda jika tidak akan digunakan untuk masa yang lama.

Dengan mengikuti langkah-langkah ini, anda dapat meningkatkan perlindungan data. Anda juga dapat menikmati kasino selamat di Mega888 dengan lebih tenang.

Trend Terkini Casino Online Malaysia

Industri perjudian dalam talian di Malaysia mengalami perubahan besar dalam beberapa tahun terakhir. Teknologi baru dan perubahan undang-undang mempengaruhi trend kasino online. Mari kita lihat beberapa trend terkini yang menarik perhatian.

Perkembangan Teknologi

Teknologi canggih menjadi sorotan utama dalam kasino online. Realiti maya (VR) dan blockchain digunakan dalam permainan. Ini membuat pengalaman bermain lebih menarik dan realistik tanpa keluar rumah.

Teknologi enkripsi dan keselamatan data juga berkembang. Ini meningkatkan keamanan transaksi keuangan di platform trend kasino dalam talian. Pemain lebih yakin untuk terlibat dalam teknologi kasino ini.

Perubahan Industri

Industri perjudian Malaysia mengalami perubahan dalam peraturan. Kerajaan memperketat peraturan untuk mengawal perjudian. Ini membantu pertumbuhan trend kasino dalam talian yang sah.

Pemain lebih suka menggunakan e-wallet untuk pembayaran. Ini memberikan lebih banyak pilihan dan keselesaan dalam transaksi online.

Secara keseluruhan, trend kasino dalam talian di Malaysia berkembang pesat. Inovasi teknologi dan perubahan industri memungkinkan pengalaman kasino online yang lebih baik, selamat, dan menarik.

Panduan Pengeluaran Wang

Apabila anda menang di Mega888 di Malaysia, penting untuk tahu cara mengeluarkan wang kemenangan. Mega888 memberikan panduan lengkap untuk memudahkan proses ini.

Langkah-langkah Pengeluaran Wang

- Log masuk ke akaun Mega888 anda.

- Pilih menu "Pengeluaran" atau "Tarik Dana".

- Pilih kaedah pengeluaran yang anda inginkan, seperti e-wallet atau perbankan dalam talian.

- Masukkan jumlah wang yang ingin anda keluarkan.

- Pastikan maklumat akaun bank atau e-wallet anda adalah tepat.

- Ikuti arahan selanjutnya untuk mengesahkan transaksi pengeluaran.

Had Pengeluaran

Mega888 membatasi minimum pengeluaran RM50 dan maksimum RM50,000. Ini untuk memastikan pengeluaran kasino lancar dan proses pembayaran cepat.

Tempoh Pemprosesan

Mega888 memproses wang kemenangan anda dalam satu hari bekerja. Tiada aduan masalah pengeluaran dari pemain kepada khidmat pelanggan Mega888.

| Kaedah Pengeluaran |

Tempoh Pemprosesan |

| E-wallet |

1 hari bekerja |

| Perbankan dalam talian |

1 hari bekerja |

Pemain mungkin perlu tunjuk bukti pengenalan diri. Ini untuk memastikan pengeluaran selamat.

"Mega888 menyediakan proses pengeluaran yang mudah, cepat dan selamat bagi memberikan pengalaman terbaik kepada para pemain."

Kesimpulan

Mega888 adalah pilihan utama di Malaysia untuk kasino dalam talian. Mereka memegang lebih daripada 90% pasaran permainan slot. Lebih dari 80% pemain dari Malaysia, Singapura, dan Thailand memilih Mega888.

Aplikasi Mega888 mudah digunakan dan dimuat turun oleh lebih dari satu juta pengguna. Mereka menawarkan banyak permainan slot, bonus menarik, dan sistem pembayaran e-wallet seperti DuitNow. Ini menjadikan Mega888 pilihan terbaik di Malaysia.

Bagi pemain berpengalaman atau baru, Mega888 adalah platform yang sesuai. Mereka memprioritaskan keselamatan, menawarkan bonus menarik, dan pengalaman bermain yang luar biasa. Ini menjadikan Mega888 pilihan utama untuk menikmati permainan kasino dalam talian dengan bertanggungjawab.

FAQ

Apakah Mega888 dan bagaimana ia beroperasi di Malaysia?

Mega888 adalah platform kasino dalam talian yang popular di Malaysia. Ia menawarkan pelbagai permainan seperti slot, kasino langsung. Sistem pembayaran DuitNow dan sokongan e-wallet TNG menjadikan pengalaman bermain selamat dan menyeronok.

Bagaimana saya boleh mendaftar akaun Mega888?

Proses pendaftaran akaun Mega888 mudah dan selamat. Anda perlu berikan maklumat peribadi dan bukti identiti. Setelah itu, akaun anda akan aktif.

Apakah kelebihan menggunakan DuitNow sebagai kaedah pembayaran di Mega888?

DuitNow memudahkan transaksi di Mega888. Ia cepat, selamat dan mudah digunakan. Kelebihannya termasuk had transaksi tinggi dan pemprosesan yang cekap.

Bagaimana saya boleh menggunakan e-wallet TNG untuk bermain slot di Mega888?

Menggunakan e-wallet TNG di Mega888 mudah. Anda hanya perlu hubungkan akaun TNG dengan Mega888. Kemudian, boleh buat deposit dan pertaruhan dengan e-wallet.

Apakah permainan slot dan kasino langsung yang paling popular di Mega888?

Mega888 menawarkan banyak permainan slot menarik. Juga, permainan kasino langsung seperti roulette, blackjack, dan baccarat popular. Anda boleh pilih permainan yang sesuai dengan gaya anda.

Bagaimana saya boleh membuat deposit di Mega888 menggunakan e-wallet?

Mega888 memudahkan deposit dengan e-wallet seperti TNG, GrabPay, dan Boost. Ikuti langkah mudah untuk hubungkan e-wallet dan buat deposit selamat ke akaun anda.

Bagaimana Mega888 melindungi keselamatan transaksi pengguna?

Mega888 gunakan teknologi enkripsi canggih dan sistem verifikasi. Ini memastikan keselamatan akaun dan transaksi pengguna. Mereka juga ikut piawaian industri untuk perlindungan data.

Apakah bonus dan promosi yang ditawarkan oleh Mega888?

Mega888 tawarkan banyak bonus dan promosi menarik. Termasuk bonus selamat datang, deposit, dan promosi bermusim. Manfaatkan tawaran ini untuk tingkatkan peluang menang.

Bagaimana saya boleh bermain slot online dengan selamat dan berkesan di Mega888?

Mega888 ada panduan lengkap untuk bermain slot online. Termasuk tips untuk menang, strategi pengurusan modal, dan nasihat bertanggungjawab.

Apakah kelebihan menggunakan aplikasi Mega888 berbanding platform web?

Aplikasi Mega888 menawarkan pengalaman permainan yang lebih baik. Ia mudah digunakan, antara muka menarik, dan prestasi tinggi. Ini memberikan pengalaman bermain yang lancar.

Creative, Entrepreneurial, and Global: 21st Century Education

Home » Blogs

How Does PISA Put the World at Risk (Part 1): Romanticizing Misery

9 March 2014

74,836

17 Comments

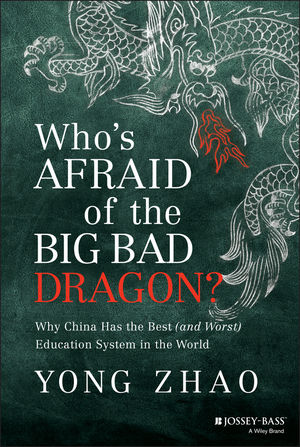

PISA, the OECD’s triennial international assessment of 15 year olds in math, reading, and science, has become one of the most destructive forces in education today. It creates illusory models of excellence, romanticizes misery, glorifies educational authoritarianism, and most serious, directs the world’s attention to the past instead of pointing to the future. In the coming weeks, I will publish five blog posts detailing each of my “charges,” adapted from parts of my book Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Dragon: Why China has the Best (and Worst) Education.

Part One: Romanticizing Misery

Andreas Schleicher has on many occasions promoted the idea that Chinese students take responsibilities for their own learning, while in “many countries, students were quick to blame everyone but themselves.” France is his prime example: “More than three-quarters of the students in France … said the course material was simply too hard, two-thirds said the teacher did not get students interested in the material, and half said their teacher did not explain the concepts well or they were just unlucky.” Students in Shanghai felt just the opposite, believing that “they will succeed if they try hard and they trust their teachers to help them succeed.” Schleicher maintains that this difference in attitude contributed to the gap between Shanghai, ranked first, and France, ranked 25th. “And guess which of these two countries keeps improving and which is [sic] not? The fact that students in some countries consistently believe that achievement is mainly a product of hard work, rather than inherited intelligence, suggests that education and its social context can make a difference in instilling the values that foster success in education”[1]

Self-condemnation Does Not Lead to High Scores

Schleicher got the numbers right, but his interpretation is questionable. There are plenty of countries that have higher PISA rankings than France, yet report similar attitudes. For example[2], more students in number eight Liechtenstein and number nine Switzerland (over 54%, in contrast to 51% in France) said their teachers did not explain the concept well. The percentage of students attributing their math failure to “bad luck” was almost identical across the three countries: 48.6% in Liechtenstein, 48.5% in Switzerland, and 48.1% in France. The difference in percentage of students claiming the course material was too hard wasn’t that significant: 62.2% in Liechtenstein, 69.9% in Switzerland, and 77.1% in France. Neither was the difference in the percentage of students saying that “the teachers did not get students interested in the material:” 61.8% in Liechtenstein, 61.1% in Switzerland, and 65.2% in France.

Moreover, the PISA report seems to contradict Schleicher’s reasoning because it finds that students with lower scores tend to take more responsibility:

Overall, the groups of students who tend to perform more poorly in mathematics—girls and socio-economically disadvantaged students—feel more responsible for failing mathematics tests than students who generally perform at higher levels [1, p. 62].

The degree to which students take responsibility for failing in math or blaming outside factors does not have much to do with their PISA performance. The percentage of students who attribute their failing in math to teachers: countries with low percentages of students saying “my teacher did explain the concepts well this week” or “my teacher did not get students interested in the material” do not necessarily have the best ranking. Conversely, countries where students are more likely to blame teachers are not necessarily poor performers.

Using Shanghai as the cutoff, the countries with the lowest percentage (below 35%) of students blaming their teachers for failing to explain the concepts well are Korea, Kazakhstan, Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, Russian Federation, Chinese Taipei, Albania, Vietnam, and Shanghai-China. An almost identical list of countries has the lowest percentage (below 41%) of students blaming their teachers for not interesting students in the material: Kazakhstan, Japan, Albania, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Russian Federation, Montenegro, and Shanghai-China. Combining responses to both questions are combined, we have the top 10 countries where students are least and most likely to blame their teachers (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1: Top 10 Countries Where Students Are Least Likely to Blame Their Teachers for Failing Math and Their Respective 2012 PISA Ranking

| Country |

PISA Ranking (Math) |

| Kazakhstan |

49 |

| Japan |

7 |

| Albania |

57 |

| Singapore |

2 |

| South Korea |

5 |

| Malaysia |

52 |

| Russian Federation |

34 |

| Chinese Taipei |

4 |

| Shanghai-China |

1 |

| Viet Nam |

17 |

Table 2: Top 10 Countries Where Students Are Most Likely to Blame Their Teachers for Failing Math and Their Respective 2012 PISA Ranking

| Country |

PISA Ranking (Math) |

| Norway |

30 |

| Italy |

32 |

| Germany |

16 |

| Slovenia |

20 |

| France |

25 |

| Austria |

18 |

| Czech Republic |

24 |

| Sweden |

38 |

| Liechtenstein |

8 |

| Switzerland |

9 |

As can be seen in the two tables, among the countries whose students are least likely to blame teachers are some of the best (Shanghai, Japan, Korea, Singapore, Taipei, and Viet Nam), worst (Kazakhstan, Albania, Malaysia), and average (Russian Federation) PISA performers. Students who are most likely to blame teachers come from countries that earn the top PISA scores (Liechtenstein, Switzerland, and Germany) and middle-level PISA scores (Norway, Sweden, Italy, Slovenia, France, Austria, and the Czech Republic).

Self-condemnation as Result of Authoritarian Education

What’s intriguing is that the countries whose students are least likely to blame their teachers all have a more authoritarian cultural tradition than the countries whose students are most likely to blame their teachers. On the first list, Singapore, Korea, Chinese Taipei, Shanghai-China, Japan, and Viet Nam share the Confucian cultural tradition. And although Japan and Korea are now considered full democracies, the rest of the countries on the list are not[3]. In contrast, the list of countries with the highest percentage of students blaming their teachers for their failures ranked much higher in the democracy index. Norway ranked first; Sweden ranked second, and Switzerland was number seven. With the single exception of Italy, all 10 countries where students were most likely to blame their teachers ranked above 30 on the Democracy Index (and Italy ranked 32nd).

One conclusion to draw from this analysis: students in more authoritarian education systems are more likely to blame themselves and less likely to question the authority—the teacher—than students in more democratic educational systems. An authoritarian educational system demands obedience and does not tolerate questioning of authority. Just like authoritarian parents [2], authoritarian education systems have externally defined high expectations that are not necessarily accepted by students intrinsically but require mandatory conformity through rigid rules and sever punishment for noncompliance. More important, they work very hard to convince children to blame themselves for failing to meet the expectations. As a result, they produce students with low confidence and low self-esteem.

On the PISA survey apps of students’ self-concept in math, students in Japan, Chinese Taipei, Korea, Viet Nam, Macao-China, Hong Kong-China, and Shanghai-China had the lowest self-concepts in the world, despite their high PISA math scores[4]. A high proportion of students in these educational systems worried that they “will get poor grades in mathematics.” More than 70% of students in Korea, Chinese Taipei, Singapore, Viet Nam, Shanghai-China, and Hong Kong-China—in contrast to less than 50% in Austria, United States, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands—“agreed” or “strongly agreed” that they worry about getting poor grades in math[5].

Emperors’ Ploy to Deny Responsibility

In other words, what Schleicher has been praising as Shanghai’s secret to educational excellence is simply the outcome of an authoritarian education.

As discussed previously, Chinese education has been notoriously authoritarian for thousands of years. In an authoritarian system, the ruler and the ruling class (previously the emperors; today, the government) have much to gain when people believe it is their own effort, and nothing more, that makes them successful. No difference in innate abilities or social circumstances matters as long as they work hard. If they cannot succeed, they only have themselves to blame. This is an excellent and convenient way for the authorities to deny any responsibility for social equity and justice, and to avoid accommodating differently talented people. It is a great ploy that helped the emperors convince people to accept the inequalities they were born into and obey the rules. It was also designed to give people a sense of hope, no matter how slim, that they can change their own fate by being indoctrinated through the exams.

Adapted from Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Dragon: Why China has the Best (and Worst) Education (Chapter 8)

References:

1. OECD, Ready to Learn: Students Engagement, Drive, and Self-beliefs. 2013, OECD: Paris.

2. Baumrind, D., Effects of Authoritative Parental Control on Child Behavior. Child Development, 1966. 37(4): p. 887-907.

[1] http://oecdeducationtoday.blogspot.com/2013/12/are-chinese-cheating-in-pisa-or-are-we.html

[2] All data from (OECD, 2013)

[3] according to Democracy Index 2012, an annual ranking of 165 countries’ state of democracy produced by international research group The Economist Intelligence Unit (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2013).

[4] Based on aggregated data from (OECD, 2013, p. 304).

[5] Based on aggregated data from (OECD, 2013, p. 310).

[…] YongZhao PISA, the OECD’s triennial international assessment of 15 year olds in math, reading, and […]

A very compelling post, Yong Zhao. Many thanks. I’d like to add a couple of comments.

There are some very real questions about how appropriate many of these country comparisons are. To state the most obvious: From the quote in your blog, Mr. Schleicher seems to be under the impression that Shanghai is China. He of course knows better. And he knows Shanghai is the wealthiest city in China. He might as well assess Scarsdale, New York and pass it off as the United States.

Or take Liechtenstein and Kazakhstan, cited in your post. The former is a fabulously beautiful and quite wealthy enclave in the Alps. It has a total population of 35,000 people, men women, and children. Its entire student population could probably fit into one large American high school. The latter: a kleptocracy presided over by the same man since it declared its independence from the former Soviet Union in 1990. He was last re-elected in 2005 with more than 90% of the popular vote. (Khazakstan’s neighbor, Azerbaijan, recently demonstrated an equally touching devotion to democratic principles. In a triumph of efficiency last October, election authorities released final election results a full day before the polls opened.Link below.)

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/wp/2013/10/09/oops-azerbaijan-released-election-results-before-voting-had-even-started/

Why is the United States being compared with nations such as this as though the comparison was in some way informative and meaningful?

A more direct point is the following: Earlier this month, after years of denying that PISA’s assessment of students in Shanghai ignored hundreds of thousands of the children of Chinese migrant laborers, Mr. Schleicher earlier this month acknowledged before a committee of the British House of Commons that PISA had failed to account for more than one quarter of the 15-year-olds in the city. (Link below to the Times (of London) Education Supplement.)

More than a quarter of Shanghai pupils missed by international Pisa rankings

http://news.tes.co.uk/b/news/2014/03/05/more-than-a-quarter-of-shanghai-pupils-missed-by-pisa.aspx

This belated acknowledgment calls into question all of the lessons we are supposed to learn from Shanghai’s educational system. It calls into question also the competence with which the PISA assessment is conducted and the integrity of the assessment itself.

Thanks again Yong. PISA testing, and the media that accompanies it, also serves to reinforce the illusion that standardized testing, à la PISA, is valid way to rank children and young people.

In an era when mass education has come to be defined (hijacked is more correct) by politically-driven initiatives like NCLB, Race to the Top, PISA, etc., the main outcome to my perception as an award-winning educator, has been harm to young learners and the education system.

The main beneficiaries have been and continue to be principals of the testing industry (now a multi-billion $ lobby force) and political advocates riding in this parade.

– Michael Maser

SelfDesign Learning (BC Canada)

You are concerned about the maturation of young adults?

200 years ago 14 year old boys were leading groups of men into battle (until a common agreement was reached between the major European nations that “it was more proper” to have a minimum age of 16 – which has since stood for many years).

I know it myself personally that many young people even now-a-days grow up in areas of high danger and extreme hardship – the “stress” of failing a test is laughable!

Next you’ll be wanting to wrap 30 years olds in diapers feeding them candy flow and lolly pops!

It just goes to show that any two data points of statistical facts can be drawn out of the set to make any argument.

Andreas Schleicher knows this, but is the master of the sound bite and these two random data points serve his purpose well.

However, to start to unpick information in any meaningful way the whole of the data must be considered (alongside the realisation that it may or may not be wholly reliable data in the first place). And that is what we should expect from someone in Schleicher’s position – not simplistic statements, nor smoke and mirrors.

[…] In this post, Zhao demonstrates one of the misleading claims made by Andreas Schleicher, who runs PISA. […]

[…] Education in the Age of Globalization » Blog Archive » How Does PISA Put the World at Risk Part 1:…. Share this:ShareLike this:Like […]

[…] In this post, Zhao demonstrates one of the misleading claims made by Andreas Schleicher, who runs PISA. […]

[…] In this post, Zhao demonstrates one of the misleading claims made by Andreas Schleicher, who runs PISA. […]

[…] How Does PISA Put the World at Risk (Part 1): Romanticizing Misery […]

I believe PISA has a number of merits and strengths and one needs to look at data and evidence in education too, just like in the other areas.

The article starts with the claim that “PISA… has become one of the most destructive forces in education today” (A)

But it goes on to only argue (and provide some good evidence) that “what Schleicher has been praising as Shanghai’s secret to educational excellence is simply the outcome of an authoritarian education”. (B)

(B) is probably correct. But far, far removed from (A).

[…] Det finns nämligen inget samband mellan huruvida eleverna “skyller på lärarna” eller inte och resultaten i PISA-undersökningen! (Vill du veta var jag fått detta ifrån kan du klicka här!) […]

[…] is a link to his blog on the topic, and here is Dr. Zhao speaking on the topic. (He also has a 2011 TED Talk you might […]

[…] “How Does PISA Put the World at Risk”, Dr. Yong Zhao » Lo que oculta el informe Pisa, Carlos Manuel Sánchez, XL Semanal, 27 abril […]

[…] » ¿Déficit democrático en los informes PISA?, Josep M. Vallès, El País, 22 abril 2014 » “How Does PISA Put the World at Risk”, Dr. Yong Zhao . » Ítems liberados de pruebas de evaluación y otros recursos, INEE, España […]

[…] » ¿Déficit democrático en los informes PISA?, Josep M. Vallès, El País, 22 abril 2014 » “How Does PISA Put the World at Risk”, Dr. Yong Zhao . » Ítems liberados de pruebas de evaluación y otros recursos, INEE, España […]

[…] How Does PISA Put the World at Risk (Part 1): Romanticizing Misery Education in the Age of Globalization […]